PlusHeart Issue #8 - Valve Software, Dota 2, and the responsibility of fandom

Despite having no interest in community management, a community popped up all the same. Now what happens when the modern marketing metagame comes into play?

This issue is important, but it also feels like I’ve written it a thousand times over a series of tweets, every six months or so.

I’ll spare you the long details:

Valve Software owns Dota 2, a competitive video game.

DotA: Allstars was a mod for Warcraft 3, and took off with a life of its own.

Valve said “hey, this mod is pretty cool. Let’s buy the rights, hire the people involved, and make a sequel.”

Valve Software has run the Dota 2 championships, called “The International” for the past ten years. It is different from a lot of other esports events — it has no ads, no sponsorships, and sources a large amount of its prizepool from the community in exchange for in-game cosmetic items.

This crowdfunding element was seen as an innovation when it was developed (TI3); fans got cosmetics that could be resold on the Steam marketplace for Steam credit, or through (unofficial/unsupported) third-party sites for real money.

The crowdfunding ballooned the prize pool yearly.

This meant that The International eventually meant that a player on the winning team could be a millionaire, or more, if they won it.

For commentators and talent, they also had in-game items to sell that gave them a cut.

This meant that all priorities for pros and talent in Dota 2 shifted toward The International.

Because of this, the opaque process for which teams got selected for The International became increasingly criticized (as it should). With so much at stake, the teams should know how they could earn their attendance.

Valve toyed with the idea of several “mini-TIs” during the year, but eventually settled on fully outsourcing “Majors” to third-party production companies, with Valve’s support.

The current system, the Dota Pro Circuit (DPC), has gone through some iterations over the years. Currently it has several regional leagues that allow teams to qualify for Majors; doing well in these leagues give you circuit points, but doing well at Majors gives you much more. More circuit points = more security to getting to TI.

However, this is where things get complicated:

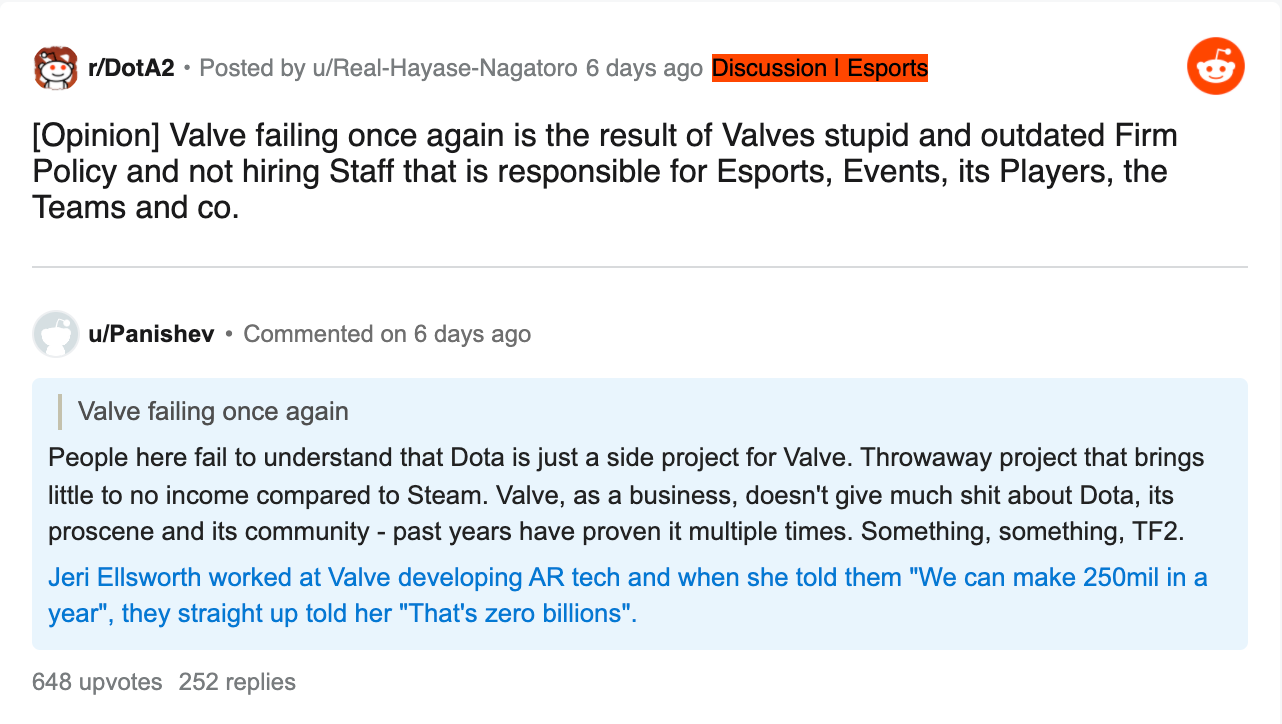

Valve has never been good about communication, both between the community and the professionals (players and talent) that make their living from the game. From the outside, Valve is a very mysterious and enigmatic company — they do what they want, when they want.

With The International, though, there was this aura around the event that gave the impression of caring and altruism. Sure, we may not know when a patch is coming, but at least we know that Valve are going to pull out all the stops to celebrate good Dota, which is something that the fans all want.

This earned them a lot of goodwill, at least from the greater community. On the inside of the professional veil, though, Valve have made it… difficult.

Because Valve are running The International outside of the bubble of “greater esports”, the same pressures that would work on other developers do not work on them. You can’t pressure sponsors or investors, because there are none. You can’t pressure employees, because it is rare that you have any public-facing ones, and the ones that do don’t have the Community Manager role. There is no CM role.

So essentially, we’re at a point where we accepted “Valve being Valve” and Valve doing what they wanted, because it at least gave us a bunch of good entertainment. For people trying to make money, they could try to make money, as long as they were in a position to attend events, as judged by Valve’s mystical scrying orb of decision-making.

Now we’re up to speed. Sort of.

COVID-19 has messed up a ton of esports worldwide, and Dota is no exception; the current system of DPC has basically never had a chance to operate under normal circumstances, and along the way it’s been a mountain of compromises.

The biggest ones have mostly been around that path to TI: when Valve announced that their first Major of this season would just be straight-out cancelled, it seemed a bit understandable considering the mess of the COVID-19 Omicron variant, and also trying to make sure that players remained healthy.

However, a grumbling started.

From Valve’s blog on cancelling the event:

Teams participating in the DPC earn points by playing in their respective Regional Leagues as well as through international competition at the Majors. Since the first Major is no longer happening, we have decided to redistribute its points to the second and third Major. This way, the balance of points between regional and cross-region play remains the same.

Essentially, this meant that players who won their DPC leagues in “Tour 1” (or part 1 of the season, followed by Major 1, followed by Tour 2, etc), would get… not a lot.

$30,000 for the eight weeks of competition, split five ways (without a cut to anyone else, like coaches, an organization, etc) is $6,000. Depending on the cost of living in your region, this is a pittance in terms of playing professional Dota — at its highest skill level — as a full-time job.

Because of TI, and because of the Majors feeding into TI, and the DPC feeding into the Majors, suddenly the house of cards has come crumbling down. Teams without security are frustrated at the lack of communication, and also are wondering “Why are we even doing this?”

It’s very rare to see just a blatant outpouring of “this sucks, here’s what we’ve got” to the public from pro players, but it happened. From Evil Geniuses1’ current Dota manager (who managed Undying previously):

At TI10, Valve held a meeting with all the teams. After explaining to us the schedule of next years DPC, two points were very clearly made.

When teams have problems, they should stop going directly to public platforms, and should instead communicate with Valve.

Valve sees TI as a passion project. They don’t gain much revenue from TI compared to the time out [sic] in, and when teams go straight to public platforms to complain about issues, it makes Valve less motivated to keep running TI.

In an ideal, and I believe achievable, world there is no problem with this. Teams should be able to go directly to valve with problems that they have, and those problems can be acknowledged, and either solved or managed in a way to create a harmonious relationship. However there is still no way for teams to communicate directly with Valve, and no information being given to teams.

As an example PuckChamp, a CIS team in good standings to qualify for the major, has players in Kazakhstan. Because of the current political situation of the country, the team and players needed to know information about the major as soon as possible, as leaving and re entering the country was not a guarantee. Their manager has been desperately trying to get in contact with Valve for weeks about this, and hasn’t received any response.

I have no call to action or solutions to suggest, because it’s all been brought up countless times. Community managers, larger hired staff, weekly updates, they’ve all been discussed in the past. Lack of communication is far from a new issue. But with the DPC system, Valve has told players that if they want to qualify to TI, their road will be far longer, more constant, with smaller prize pools than the pre DPC majors. The least we could ask for in return is open communication from Valve.

“That’s zero billions”

This newsletter took a bit to get going, but this is where I want to make my point: the ongoing culture shock between what consumers see in other companies, versus what they experience from Valve.

To a lot of people, the awakening to how Valve care (not necessarily how much they care) is rough because it flies in the face of what brands have taught them over the last decade: fans and enthusiasts are king, and they have small amounts of ownership and influence over how it develops.

To Valve, it isn’t quite a malicious relationship, but they’ve removed the typical power structure of the brand-to-stan pipeline: they know people are going to play their games and use Steam regardless of what they do in terms of public-facing community building. They’d rather not do that management and interaction, so they don’t.

However, when events like this occur, people get hurt emotionally, because they believed that Valve was their friend — not literally, but in terms of forming a connection with Dota as a whole, that pseudo-friendship serves the same purpose.

After all, Valve fought for Dota. They de-tangled the messy nature of who owned the rights to it, between Blizzard (whose Warcraft III: Frozen Throne game housed the original DotA: Allstars mod) and Riot Games (who filed an opposing trademark for “Dota” to Valve’s, since they owned DotA-Allstars, LLC, as a subsidiary).

If developing Dota 2 was a purely corporate move, and Valve wanted to squeeze it for all it was worth, it did not present that image from the start.

Dota 2 felt like an alternative to a gaming landscape that its fans didn’t fit into, or didn’t want to fit into: its community carried the weight and resentment for League of Legends being more popular, more well-liked, and more accepted as a “cool” gaming property. Maybe they didn’t like its art style or mechanics, but felt they had to because it was where their friends were, or “it got all the good stuff” in terms of fanworks, merchandise, porn, or promotions.

Riot had antagonized the DotA: Allstars crowd through a hostile takeover of forums, URLs and assets in order to promote League of Legends. That resentment festers in people, and it has led to an adversarial nature that is baked into the DNA of the Dota 2 community.

And while Dota 2 might not have K-pop, it did have Valve — Valve cared about things like The International, and enabled the community to keep their game relevant by consistently contributing to the largest prize pool in all of esports. That validation and relevance meant something to them.

So when the odd crack appeared in the relationship, it became easy to excuse Valve’s increasing habits of whale-hunting, developing exclusive cosmetics that were inaccessible to a casual player without paying money, or compromising the game’s aesthetic. Valve’s actions still meant good Dota, and still carried that spirit of “we fit in here where we don’t otherwise.”

Enabling that DIY, independent, alternative spirit makes a connection grow, and in turn, breeds attachment, and an immense amount of goodwill (as mentioned in Issue #6). The community got to take pride in how they supported the game, because it felt that they owned part of that success. Despite not being mainstream-friendly and not “for casuals”, they still had a place at the greater esports table.

So… what happens when you start seeing things to the contrary of that image you’ve built up in our head? What happens when suddenly you’re reminded that the flaws you attempted to hide (or remain ignorant of) were always there, and they’re coming back, louder than ever?

Instead of a compromise in how an in-game hat is designed, suddenly the consequences are a lot more severe:

Valve sees TI as a passion project.

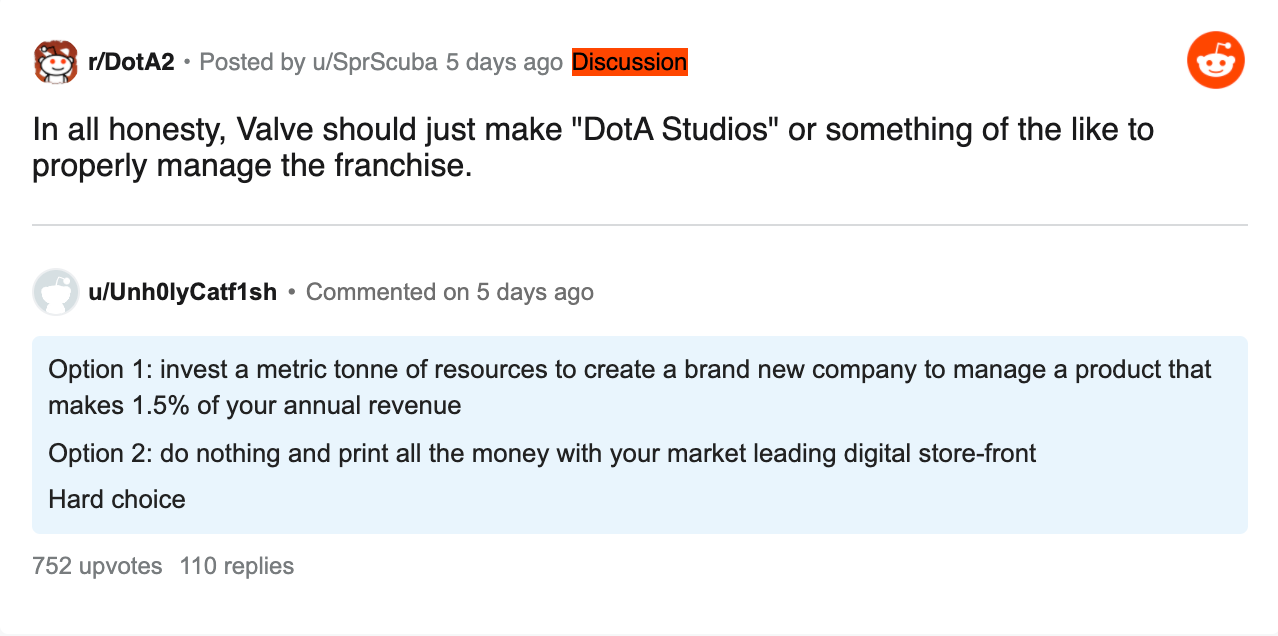

To Valve, The International — and by extension, Dota esports — is something that that can be abandoned, when they feel like it, regardless of the consequence to people outside Valve.

The fans’ attachment and feeling of belonging does not matter. Players have little leverage to unionize, as lower-tier players have different interests than higher-tier ones, and compromising on those needs render efforts extremely difficult; since Valve have sold the dream of The International, you end up with “scab players”, who are just happy to be there.

To Valve, teams and players are interchangeable and expendable, and if The International can’t run without them, that’s when it will die.

What’s left

It’s hard to advise regular people on what to do about this.

I want to be able to encourage a degree of cynicism and distance between yourself and emotionally connecting to any brand, because this kind of thing can be shattering. Taking the company out of it, the idea of someone suddenly saying “we don’t care about you, we never cared about you, you knew this, and you allowed it to happen” is… a tough thing to work through, especially when it’s true.

Esports don’t develop without passion, and the interest of the owning company is always going to be different than the person who just wants entertainment — it’s part of a fan’s job to recognize this.

But for some reason I have a hard time sitting here, pointing the finger at pros, community and talent and just saying “this is partially your fault for caring.” Fuck that. I was there too, and the idea of “when it’s good, it’s really good” is especially strong with Dota.

That idea of finding your place is something that’s I’ve thought about a lot lately in my personal life, and especially with the broadening of gaming culture, it’s easy to feel alienated by what’s the most popular — there’s just so much of it, and it feeds off of itself to perpetuate game development memes in design and aesthetic.

So when you find your place, and you feel safe in it, and you have this juggernaut company (no pun intended) telling you “You know what, you’re right. I’m going to stick my neck out to craft a place for you,” you trust that. It gives you hope.

That hope meant that the community stuck their necks out for Valve, in turn: Beyond the Summit2 started as a way for people to watch Dota in Asia that no one else was covering in English. They spread the love of the game and nurtured the talent that communicate it today. When the Fortnite World Cup dropped a bigger prize pool than any International, Dota rallied to “take the title back.” Despite the density of “how to play Dota”, the community created a tutorial to coincide with a Dota Netflix series’ launch — they were so tired of begging Valve for a better New Player experience, they just made one themselves.

To make peace with accepting less out of protection for yourself, even though it’s right there, and you know what it’s capable of, is hard. The entity that can make it happen isn’t going to — that’s something people are going to have to let go.

Despite every stoic pundit that’ll say “you should’ve known better,” I don’t think it’s stupid to have hope that it could be different.

I’d write to you from that position, detached from the possibility of being actually affected, but I’d be lying to both myself and you if I said it didn’t matter.

Aftercare

The main reason this kind of fascinates me is because there’s a discussion to be had about the responsibility that a brand has when they’re fostering emotional connection.

Whether they’re doing it on purpose to the degree that it affects peoples’ lives turns into a plausible deniability thing: “Sure, we implied things, or meant the best, but we didn’t say you had to mortgage your house to buy for this event!” It basically becomes a semantics argument in order to deflect from culpability.

Ironically, despite Valve wanting to keep away from the community management game, the passion still shone through — that impression of caring still occurred, because the product itself was special, and born from the community spirit of modding. That spirit feels very rare these days.

Whether they didn’t know what they had (doubtful) or didn’t understand that spirit (ultra-doubtful), it ironically feels difficult to struggle against the metagame of how brands and fandoms operate — I don’t think there’s a going-back point from fans feeling a level of ownership, attachment and entitlement when it comes to their entertainment.

While Valve has updated that something is happening with regards to the end of this DPC Tour, I feel like the burnout has set in and more people are becoming aware of what they need to do to manage their expectations. It feels like a breaking point, and every time something like this happens, it gets worse.

The above comment really kind of hit me because there’s this resignation, which also means other people are thinking it, too. The sad thing is that we can easily picture a conversation happening at Valve:

“Dota has peaked, and it’s in its retention phase. It won’t be a mainstream phenomenon, as it’s missed its window for that. We’re going to lose a lot of players [like the ones above] but we might still have some years of revenue from the whales. When those start to go, we can probably shutter it, chalk it up as an overall success, and move on.”3

It’s cold — it’s realistic, but it’s cold. It’s a business decision, and one that other companies make all the time. We (as fans) thought we had something better, though; it felt that we could kind of dodge that ugly reality of it still being a business.

We thought we had something more than that, and it’s scarier still thinking that we’d have to try to find something to replace it.

Even if something did, we’d still have that unease. We’d erect a defensive wall to protect from disappointment: the possibility of it happening again is still there, and it’s up to us to take the risk.

Housekeeping

Really proud of how this one came out.

I’m still streaming Paper Mario 64 on Saturdays.

Join the Discord for announcements, event notifications, etc.

Disclosure: I have worked for EG in the past, but not with the person involved.

Disclosure: I have done contract work for Beyond the Summit in the past.

And yes, I realize the irony of projecting this onto a company I have no internal knowledge of. Valve don’t want communicate because they feel burned by response whenever they do, and that’s something I’m arguably continuing, here. But I don’t know if a company right now has that luxury of just saying “Nah, don’t want to deal with that” while still expecting a level of fandom attachment.